It took a while to sink in...

It had never crossed my mind that quality television programming could exist on networks other than the CW and Lifetime...

Yet, this past Sunday, I had a jarring -- perhaps transformative -- revelation as I lounged before my boob tube to take in the Mad Men marathon on AMC. Okay, so I needed an extra nudge from an occasional reader to discover for myself what all the buzz was about. The important thing is that I swallowed up my willful ignorance and indulged in the television equivalent of a marzipan orchestra.

Thirteen hours later, as I nurtured my bed sores, I was overtaken by a sensation of woozy euphoria tinged with a modicum of rueful anger over the fact that other television programming existed (with the exception, naturally, of Gossip Girl and Lifetime original programming).

Perhaps it was the savory dialogue, perhaps it was beautiful Jewess Rachel Menken, perhaps the way each shot was perfectly, colorfully framed as if it were itself a maquette drawn up by Sterling Cooper's Art Director Salvatore Romano.

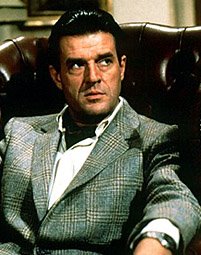

What makes the series for me, however, are the strength and complexity of the exquisite anti-hero Don Draper as well as the tension generated by feminine aspirations in this male-dominated world, all set against the individualistic ethos propagated by Ayn Rand and adopted by the movers and shakers of the Mad Men microcosmos. In essence, then, Mad Men achieves for me the transposition of the oeuvre of that greatest American writer of the 20th Century, Mickey Spillane, (Okay, maybe Nathanael West gets points in this category, too) onto the cutthroat world of advertising. Certain scenes appear to uncannily capture in pictures the lights and darks of urban society that Spillane expressed in the bare bones poetry of his descriptions.

But whereas Spillane's Mike Hammer series seems to vaunt the triumph of individual morality over the blurred lines of an evolving society, Mad Men clearly mocks this effort as hubris.

Don Draper, himself, exemplifies this startling reversal. We are led to understand, early on, the Draper has a life scinded in two by wartime service; his pained handling of his purple heart hints at pained memories of brave service brushed under the carpet of his current achievements. This dynamic is reminiscent of Spillane's masterpiece, The Long Wait. There, Johnny McBride, amnesiac seeks to clear his name of smears which he can't recall, his life split between his actions and a forgotten past. However, just as McBride recovers through the novel a continuum of valor that justifies his current identity, we eventually discover the calculated cowardice and flight from identity that enabled Draper's ascension. This delightful ambiguity doesn't so much reveal a weakness in Spillane's narrative as it demonstrates Mad Men's ability to adapt its account of the transitional 60s to our society's self-perception in this 21st century.

Similarly, while strong women abound in the Mike Hammer adventures, their presence generates fear, distrust and anxiety. At first seduced, Hammer must conclude by reestablishing order. Thus the classic closing lines of I, the Jury:

"How c-could you?" she gasped.Navigating the emerging social mobility of women in Mad Men, however, hardly comes easy to the aforementioned mad men. Betty Draper, Peggy Olson and Rachel Menken each expresses her desire for self-realization, and Don Draper's relationship with these women becomes a wrestling match with the status quo, the burden of passion, and marketplace calculations. The resulting consequences of belittlement, enabling and surrender mark the stark contrasts borne of these tensions in the private and public sphere. One would be hard pressed to find another program on television that traces as sophisticated a portrait of the power dynamics between the sexes.

I only had a moment before talking to a corpse, but I got it in.

"It was easy," I said.

Another one of the shining achievements of Mad Men is that, while so many programs strive for critical acclaim and authenticity through the illustration of brutal violence, the maturity of Mad Men is to portray a world where our demons and our valor express themselves in the muted betrayals and victories of personal ambition -- where the drama is generated not on the criminal margins of society but at its consensual core.

Finally, after countless hours spent watching television over the course of several years, one is once again reminded of the poverty of American fiction and the need to confront the truth that our country's greatest storytelling talents have apparently migrated to film and TV.

No comments:

Post a Comment